Several have been killed and hundreds more wounded in the deadliest outbreak of violence along the 2,600km Afghanistan-Pakistan historically disputed border in recent years. The clashes erupted on October 11 after Islamabad struck Kabul and southern Afghanistan, accusing the Afghan Taliban—who took power in 2021—of harboring Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) militants. The Taliban denied the claim, as TTP fighters continued attacks on Pakistani troops.

For over two decades, Pakistan has sheltered the Taliban, allowing them to launch assaults on the US-backed Afghan republic, even as the Afghan Taliban’s growing ties with India—Pakistan’s nuclear power rival—reshape the region’s balance of power.

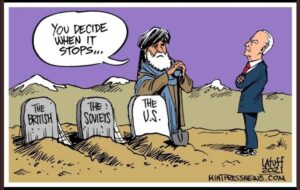

For more than two decades, Washington chased the illusion that it could remake South Asia—a project born of power, sustained by faith, and undone by hubris. Marching into Afghanistan with soldiers and slogans of democracy, the U.S. sought to tame a region defined by tribal loyalties, porous borders, and rival empires. But in the shadow of the ragged mountains, geopolitics—not ideals—decided the terms of reality.

Today, the wreckage of that ambition still shapes global power. The Taliban’s return, Pakistan’s turmoil, and China’s advance reveal the true cost of American overreach—a reminder that in the borderlands of Afghanistan and Pakistan, empire met its limits.

From the outset, Washington misread Afghanistan—its terrain, its politics, its history. Blinded by counterterrorism and idealism, the U.S. believed force and nation-building could forge stability. But Afghanistan was never just a battlefield; it was an empire’s graveyard, where geography and tribal loyalties outlast every imported vision of democracy.

When the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001, it sought vengeance for 9/11 and dreamed of remaking the country in the West’s image—a mission wrapped in both morality and strategy. But Washington ignored history’s warnings. The British failed in the 19th century, the Soviets in the 1980s—and yet another empire believed it could succeed where others had fallen.

Afghan power brokers quickly learned to turn the foreign presence to their advantage. The U.S. war on terror morphed into an open-ended occupation, blurring combat with political engineering. By empowering warlords and militias, Washington built a corrupt, dependent state—one sustained by dollars and protection, not legitimacy. Beneath the facade of progress, tribal loyalties endured, the Taliban regrouped, and Pakistan quietly ensured Afghanistan would never stand fully on its own.

The American misreading lay in treating Afghanistan and Pakistan as separate wars. In reality, they were one conflict divided by the Durand Line—a colonial boundary that split Pashtun tribes on paper but not in practice. Washington expected Pakistan’s loyalty; instead, Islamabad played both sides, aiding the U.S. while sheltering the Taliban to secure leverage after America’s exit. For Pakistan’s generals, Afghanistan was strategic depth against India; for Washington, it was a test of liberal interventionism. The two visions were never meant to coexist.

The illusion of control endured as Washington mistook tactical victories for strategic success.

Drones could kill fighters, but not the conditions that bred them. Each strike fueled resentment, each raid exacerbation it. The war became self-sustaining—American power lethal in force, but powerless to shape lasting stability.

Over time, talk of victory gave way to euphemisms like “sustainable presence” and “conditions-based withdrawal”—decline disguised as perseverance. Pakistan deftly leveraged its position, reminding Washington of its supply routes whenever pressure rose.

Each crisis ended with concessions, funneling billions in aid despite clear duplicity. What was framed as necessary engagement only deepened dependency and revealed U.S. weakness.

The illusion of control became strategic paralysis. The U.S. could neither win nor withdraw cleanly, eroding credibility. Allies saw its struggles against a fragmented insurgency; rivals saw the limits of American resolve. Meanwhile, China expanded through the Belt and Road Initiative, Russia reasserted in Central Asia, and Iran extended its influence westward.

Once the unchallenged arbiter of global order, the U.S. became mired in a peripheral conflict that drained resources and credibility. Afghanistan’s tragedy was not just military—it was conceptual. Washington tried to impose democracy from the outside, ignoring that power in fragile states flows from the bottom up. The result was an unstable hybrid, neither democratic nor functional.

American advisers spoke of winning hearts and minds, but their actions often did the opposite.

Local leaders took U.S. aid, pledged loyalty, and played both sides. Blinded by optimism, Washington mistook compliance for partnership. When the Taliban returned in 2021, it was not due to newfound strength, but because the U.S.-built state was fragile—its army crumbling almost overnight. Two decades of effort collapsed in 11-20 days.

The chaotic, desperate, and globally televised withdrawal from Kabul became the defining image of America’s strategic decline.

Even as helicopters lifted off Kabul, Washington’s misreading persisted. Officials framed the withdrawal as a pivot to great power competition, as if leaving Afghanistan closed a chapter. But geopolitics offers no clean exit. The frontier remembers. The vacuum became a playground for Pakistan, China, Iran, and Russia—each recognizing what Washington ignored: Afghanistan was never about ideology, only leverage.

The U.S. illusion of control over the Pakistan-Afghanistan frontier exposed a deeper flaw: the belief that military power can replace local understanding and that moral purpose can override history. Power without realism breeds fragility. The Afghan war showcased exhaustion over resolve, dependence over dominance—and the same dynamics now echo wherever America’s reach exceeds its grasp.

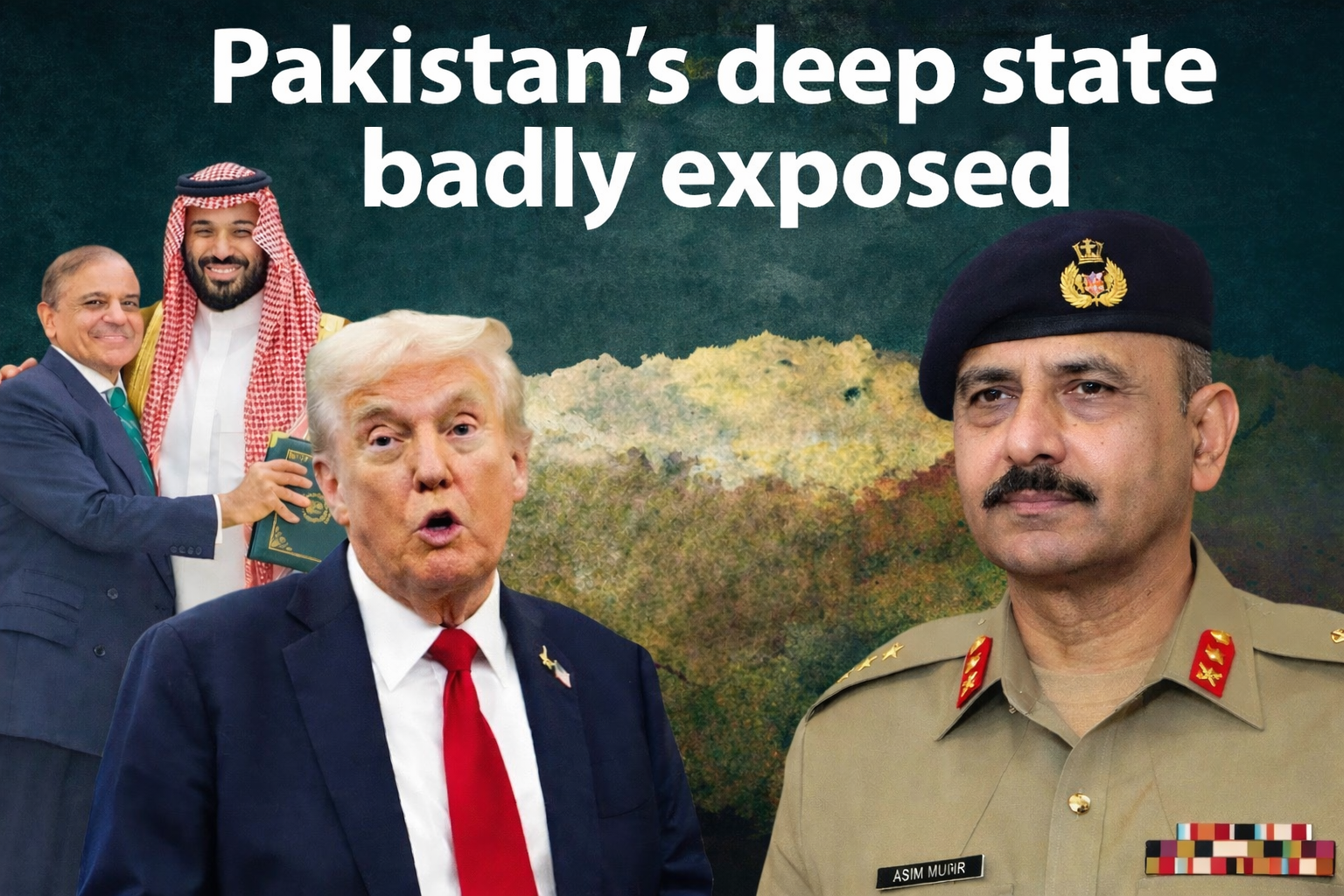

Pakistan’s alliance with the U.S. was defined by calculated dependency, mutual deception, and strategic survival. From the Cold War to the war on terror, Islamabad mastered extracting maximum gain from Washington’s ambitions while quietly pursuing its own regional agenda. For Pakistan’s military, partnerships were never ideological—they were leverage. The Americans sought allies; Pakistan sought security, aid, and influence.

The U.S.-Pakistan relationship was decades of cooperation shadowed by distrust—a transactional alliance serving short-term goals but sowing long-term instability. Nowhere was this more costly than in Afghanistan. When the Soviets invaded in 1979, Pakistan became Washington’s frontline, with the ISI channeling arms, training, and funds to the Afghan mujahedin.

Billions flowed into Afghanistan under the Reagan Doctrine, with little oversight. The ISI directed U.S. aid to factions that served its own strategic goals—Islamist groups tied to Pakistan’s security apparatus. The calculation was clear: a fragmented, Islamist-dominated Afghanistan would resist India and remain dependent on Pakistan after the Soviet withdrawal.

For Washington, the goal was defeating Moscow; for Islamabad, it was shaping the postwar balance. When the Soviets withdrew in 1989, the U.S. lost interest, leaving Pakistan—with weapons, militants, and refugees—as the de facto power broker in Kabul’s political vacuum.

Predictable chaos followed. Competing warlords tore Afghanistan apart, paving the way for the Taliban—a movement promising order and aligned with Pakistan’s strategic and religious vision. The ISI backed their rise, viewing them as a reliable proxy. By 1996, the Taliban controlled most of the country, harboring jihadist groups including al-Qaeda.

After 9/11, the U.S. returned, turning again to Pakistan under General Pervez Musharraf. Washington demanded that Islamabad sever Taliban ties, aid counterterrorism, and provide logistical access. Musharraf agreed, swayed by the threat of retaliation and the lure of financial support. Yet beneath the surface.

Pakistan pursued a dual strategy: publicly joining the U.S.-led war on terror while privately maintaining ties with the Taliban and other militants to retain influence after America’s withdrawal. This was not duplicity but strategy—driven by fears of India and regional instability. The ISI’s support for the Taliban, Haqqani network, and other groups was part of a long-standing logic of asymmetric warfare.

Conventional conflict with India was impossible, so Pakistan relied on irregular warfare—a cheaper, deniable way to project power. For Washington, this was intolerable; for Islamabad, it was survival. Tension defined two decades of U.S.-Pakistan relations. Pakistan provided supply routes, allowed drone strikes, and captured al-Qaeda figures, while Taliban councils operated openly. U.S. complaints remained private, as cutting aid risked losing critical logistics.

The fragile partnership persisted: Pakistan needed American aid, the U.S. needed Pakistan’s geography. The 2011 discovery of Osama bin Laden near a Pakistani military academy shattered trust. Yet even after U.S. forces killed him without warning, the alliance endured. Aid flowed, drone strikes continued, and Pakistan balanced cooperation with strategic noncompliance, remaining indispensable but never fully compliant.

The double-edged U.S.-Pakistan alliance devastated both countries. In Afghanistan, cross-border sanctuaries let the Taliban survive; every surge or counterinsurgency met the same reality—the enemy could retreat and return. In Pakistan, militant proxies turned inward, with the Pakistani Taliban waging deadly campaigns that destabilized the state.

Economically, billions in U.S. aid failed to spur growth. Corruption, mismanagement, and global suspicion left Afghanistan and Pakistan dependent on outside patrons—first Washington, now increasingly Beijing—while its reputation suffered under the weight of duplicity and terror financing.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a flagship of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, offered Islamabad infrastructure and investment. But it also bound the country more tightly to Chinese strategic objectives. In trying to balance between great powers, Pakistan risked becoming a pawn rather than a player. For the United States, the partnership with Pakistan exposed the limits of coercive diplomacy and the dangers of outsourcing regional strategy to unreliable allies.

The saga of Afghanistan and Pakistan underscores the limits of power divorced from local understanding. Decades of intervention revealed that military might and financial aid cannot substitute for legitimacy, nuanced diplomacy, or respect for regional dynamics. Strategic overreach not only undermined American credibility but also created vacuums exploited by rivals, entrenched instability, and empowered proxies whose loyalty was always conditional.

Ultimately, the Afghan experience is a cautionary tale: ambition without realism produces fragility, and external influence can reshape landscapes—but never rewrite the enduring logic of history, geography, and culture.

Views: 34