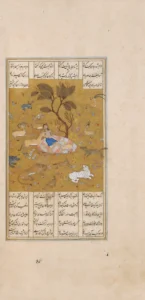

When family and social pressures prevented Majnun from marrying his beloved Layla, his heartbreak drove him to the wilderness, where he found solace among wild animals. The 7th-century Bedouin classic, Layla and Majnun, tells of his descent into madness — his name itself means “mad” — and his flight from the company of humans to animals who provided him with comfort, protection and companionship.

The profound relationship between humans and the natural world is part of the Aga Khan Museum’s Life on Land exhibition, which explores sustainability and humanity’s enduring connection to animals, water and the land. A striking manuscript from Nizami Ganjavi’s Khamseh (Quintet), a renowned literary work of Persian poetry, shows Majnun seated in a mountainous landscape, surrounded by protective creatures: a lion, hares, gazelles and horned ibexes. Exhibition curator Bita Pourvash said that Majnun’s story illustrates how nature can provide emotional and physical support during times of hardship, a relationship that remains as vital today as it was centuries ago.

The poetic couplet within the manuscript captures Majnun’s intimate bond with the wilderness:

“With a group of wild beasts taking refuge like Majnun from this oppressive world,

My time of getting acclimated to the meadow of sorrows is drawing closer.”

The painting belongs to a manuscript of Khamseh, written by Persian poet Nizami (died. 1209). The copy at the museum is from early 16th century and is painted by Ghiyath Mudhahhib, in Shiraz, Iran. Majnun in the wilderness- Museum Collections Themed Installation: Life on Land.

As part of the Aga Khan museum’s commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by Canada in 2015, Pourvash said the Life on Land installation highlights how animals and nature were celebrated in Islamic art, reflecting a deep respect for the natural world.

The exhibition connects visitors with themes of environmental preservation and promotes awareness of humanity’s responsibility to care for life on Earth, she added.

Upon entering the exhibition hall at the museum, your eyes are immediately drawn to a large text panel on the wall near the entrance, accompanied by a small image of a gazelle. It emphasizes the importance of protecting and respecting life on Earth, setting the tone for the exhibit.

Displayed alongside other artworks in a spacious hall, the installation features a diverse collection of paintings, manuscripts, pottery and carved artifacts from the Islamic world.

“Home to a growing collection of over 1,200 masterpieces, including manuscripts, paintings, ceramics and textiles from the 9th to the 21st century, the museum presents and collects art from historic Muslim civilizations, as well as contemporary Muslim communities and diasporas around the world,” Pourvash said. “The core of the museum’s permanent collection spans a vast geographic area, from Spain and North Africa in the West, across the Middle East, to South Asia and China in the East.” Another exhibit highlight is a 12th-century kilga from medieval Cairo — a carved marble base designed to hold an unglazed earthenware water jar. Together, they served to store clean water while minimizing waste.

A 12th-century kilga from Cairo, Egypt. This marble base held a porous water jar, naturally filtering clean water while preventing waste. Photo by Abdul Matin Sarfraz for Canada’s National Observer.

The jar’s porous walls allowed water to seep through, naturally filtering out impurities. The clean water would then collect in the kilga’s front trough, where it could be easily accessed. Pourvash said this system was a unique innovation in medieval Cairo, a city reliant on the annual flooding of the Nile, whose waters were often muddy and filled with impurities.

Complementing the kilga is a 16th-century marble and sandstone fountain, likely used in the reception hall of an Egyptian home. While the central portion dates to the 16th century, its surrounding design was restored in the 19th century, showcasing the continuity of craftsmanship across generations, Pourvash said.

A 16th-century marble and sandstone fountain, likely used in the reception hall of an Egyptian home. Restored in the 19th century, it highlights the enduring craftsmanship and the vital role of water in connecting communities to their environments across generations. Photo by Abdul Matin Sarfraz for Canada’s National Observer.

This fountain was more than just practical, explained Pourvash. It served as gathering points for communities, whether for worship, chores or conversation, highlighting the importance of shared resources. It reflects the ingenuity of earlier civilizations and serves as a reminder to cherish natural resources, protect clean water and maintain harmony with the world — principles that are just as relevant today, she said.

According to Pourvash, water has shaped Islamic architecture for centuries, inspiring fountains, pools and channels that provide relief in arid climates, while symbolizing life, purity and spirituality.

The exhibition, which started in July 2024, runs until February 2025.

Source: Canada’s National Observer

Views: 43